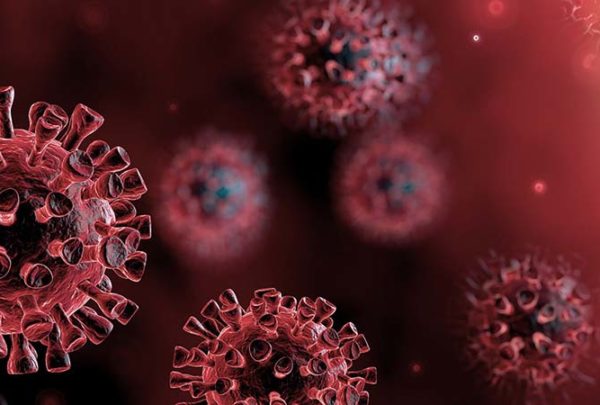

The COVID-19 pandemic has elevated the need for the healthcare industry to rethink not only our emergency preparedness program but also our overall ability to respond effectively to public health emergencies. While the United States is relatively well-trained clinically to deliver patient protocols associated with scenarios such as bioterrorism, botulism, anthrax, and COVID-19, we have been made painfully aware that our infrastructure and resources cannot appropriately support the delivery of that care. As such, the lack of our overall preparedness as a country has caught us, the world’s wealthiest nation, embarrassingly off-guard and plunged us into a health catastrophe and perhaps an economic disaster that will most likely alter our healthcare response and socioeconomic structure.

With federal funding, volunteer responses, and local support, many of the hospitals and communities hardest hit by the contagion have been able to augment and meet the surge by deferring services and implementing crisis standards of care. At the same time, hospitals in many locations have been able to easily absorb the first wave of infections and continue providing lifesaving care to both COVID patients and others with life-threatening emergencies. However, regardless of the severity of infections, our healthcare system and citizens have paid a high price. Not only have healthcare organizations sustained huge financial losses, but the wellbeing of patients and healthcare workers has been put at unacceptable levels of risk. So how do we prepare ourselves to meet the demand for the expected future waves of infections?

One of the first steps we can take in reversing this trend is to work together to actively respond appropriately to the current COVID-19 outbreaks while proactively planning for an expected reemergence once transmissions have leveled. The many vulnerabilities of our healthcare system have been made painfully apparent, and longer-term structural reforms are necessary to sustain healthcare systems into the future. It is imperative that we, as an industry, recognize our weaknesses and proactively work to close the gaps as quickly as possible to try to avoid another socioeconomic disaster during the next wave. Moving forward, organizational leaders can start to plan their response by reassessing their capabilities to respond effectively to the following key issues.

How can we better coordinate the healthcare response to COVID-19 or the next pandemic?

Hospitals need to work with each other, emergency medical services, and public health agencies to develop a plan to distribute patient load optimally. The plan should include coordinated staffing, resources, and implementation of crisis standards of care. Without this coordination a hospital could be completely overwhelmed, resulting in unnecessary deaths, while a neighboring hospital has plenty of excess capacity.

The United States needs more hospital surge capacity. Market forces have driven the number of staffed beds to a level that provides very little surge capacity, and many small hospitals in rural communities have closed. This makes the country vulnerable to unpredictable surges in volume, whether from an epidemic or from another kind of disaster. Local, state, and federal governments all have an interest in adding surge capacity.

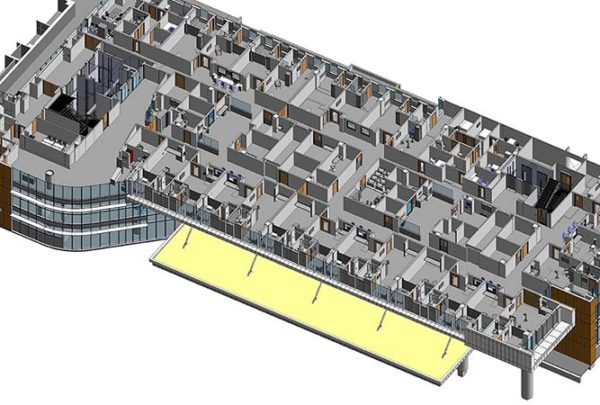

Can you respond to an increase in bed capacity?

Although we do not yet have planning assumptions or tools for COVID-19, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed FluSurge 2.0, which can be used in conjunction with planning assumptions from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to guide planning for both a moderate and severe pandemic. The default assumption is based on the 1968 flu outbreak, but it can be modified to correspond to the HHS planning assumptions to project impact.

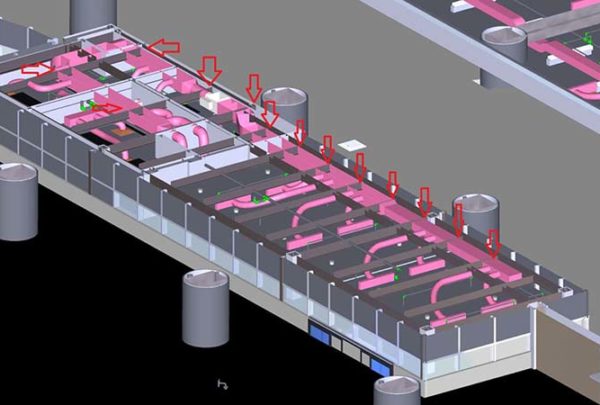

Until planning assumptions are developed, organizations can begin planning their response based on the following assumptions. Organizations should be prepared to make at least 30% of licensed bed capacity available for COVID-19 patients on one week’s notice. In most situations, about 10-20% of a hospital’s bed capacity can be mobilized within a few hours by expediting discharges, using discharge holding areas, converting single rooms to double rooms, and opening closed areas, if staffing is available. Another 10% can be obtained within a few days by converting flat spaces, such as lobbies, waiting areas, and classrooms. Collaborate with your local and regional leaders to coordinate plans to make at least 200% of licensed bed capacity in the region available for COVID-19 patients on two weeks’ notice.

Have you embraced the CDC Guidelines for infection prevention?

The CDC regularly updates guidelines on its website for infection prevention and control in healthcare settings. These recommendations, which cover topics such as ways to reduce exposure opportunities, patient isolation, staff training, infection prevention and control precautions, and environmental infection control, should be reviewed and implemented by all healthcare organizations. Consider the issues below to determine how prepared you are to control an outbreak.

- Can you limit the accidental contamination of the hospital environment by immediately implementing a respiratory program and providing simple surgical masks for everyone entering the facility (staff, patients, and visitors) during a surge?

- Can you prevent staff from getting infected by training healthcare workers on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control procedures?

- Do you have consistent access to enough proper PPE and other materials to prevent transmission, such as hospital-grade disinfectants and hand sanitizer? No agency of government is responsible for tracking supply or manufacturing capacity for PPE, and manufacturers are not required to report this information. You as an organization need to be proactive in your response.

- To determine near-term PPE needs, forecasting scenarios should be used at all levels (including alternative PPE supplier options) to get ahead of possible absolute shortages.

- If PPE supplies are not adequate to permit their use under conventional standards, back-up options should be identified in line with crisis standard-of-care guidelines (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html) to use PPE in ways that diverge from normal practices.

- Can your supply chain secure the resources needed to care for a second or third wave of COVID-19 patients? If not, work with your supply chain executives and vendors proactively to ensure you have an adequate stockpile of needed supplies.

Read Part 2 to learn how you can support your staff members during health emergencies.