Given Haskell’s complete commitment to safety, it seems only right that the company’s most recent patent should come on a device that will save lives. Given Gary Weiler’s personal experience dealing with the type of tragedy that now can be avoided, it’s only right that he be the inventor.

The device is called RAPTOR, which stands for Remotely Activated Pressure Testing, Observation & Recording. RAPTOR enables safe, efficient and remote pneumatic pressure testing of piping systems, revolutionizing the industry standard by mitigating risks and improving productivity.

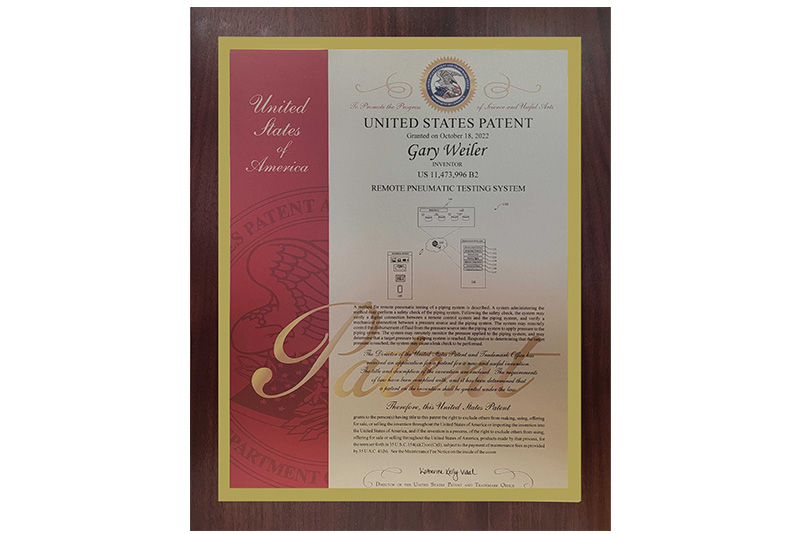

Since he entered The Big Pitch 2020, the first Shark Tank-style competition staged by Dysruptek, Haskell’s innovation and venture capital arm, Weiler has seen RAPTOR go from a sketch on a napkin to a PowerPoint presentation to a design and prototype to a minimal viable product to U.S. Patent No. 11,473,996.

Before winning the company’s support and Dysruptek’s guidance, it was under development in Weiler’s mind for more than a decade.

“It's a thing that's been near and dear to my heart for many years,” he said. “And unfortunately, it got to that point because of a fatality as a result of pneumatic pressure testing.”

Weiler is Haskell’s Senior Quality Subject Matter Expert for welding, which means he is involved in all operations that encompass welding pipes, utilities, sanitary lines and all pressure testing, be it hydrostatic or pneumatic.

It’s a pneumatic testing mishap that eventually gave rise to RAPTOR.

In April 2009, Weiler was the construction manager on a project for a different contractor. One day, as the site was closing down, he took his final walk of the premises to make sure everyone was gone.

He was back in his office finishing paperwork when he heard an unusual noise that he described as a “thump.” He looked out the window and saw dust flying, so he left the construction trailer to investigate. The dust rose from an area where a subcontractor crew was installing a six-inch PVC cooling water pipe over a run of about 600 feet. Once he got close enough, he saw a man slumped over the pipe and called 911.

“It turns out that this crew of three or four guys had left and, I guess, got together and decided, ‘If we pressure test this tonight, we can start doing our tie-ins in the morning,’ Weiler said. “Normally, this little crew was very diligent about keeping me informed. The foreman and I were always the first to be on-site and the last to leave, and never once did he fail. Except for that day.”

That day, after gluing the joints on the cool April morning, they returned to test their work at the end of the day by using an air compressor to pressurize the pipe and soaping the joints to detect leaks. There was no means of communication or line of sight between the person running the compressor and the other end of the pipe, and there was no gauge to display the amount of pressure.

They soaped about three-fourths of the way down with no problem. Near the other end, the foreman was soaping a joint that angled 45 degrees down when the pressure broke through. A piece of the failed joint hit him in the forehead and killed him.

“I spent years thinking about that every time we came across a situation where it would make sense to do a pneumatic test,” Weiler said.

‘We Have to Do Better’

Now, fast-forward a decade. Weiler had come to work for Haskell, which was contracted to design-build several facilities for rocket maker Blue Origin in Merritt Island, Florida. One phase required pressure-testing a system to 9,350 pounds per square inch (psi), which, should it explode, represented the equivalent of 127 pounds of TNT – the equivalent of more than five M795 155 mm howitzer shells or 872 Mk2 hand grenades.

“We had a 400-foot kill zone around there and got everybody out except for the three men operating the equipment,” he said. “I was thinking the whole time that this is really dangerous. That really kicked the thought process into overdrive that as an industry we can do better than this. We have to do better.”

It occurred to Weiler that the answer was in the palm of his and virtually everyone else’s hand.

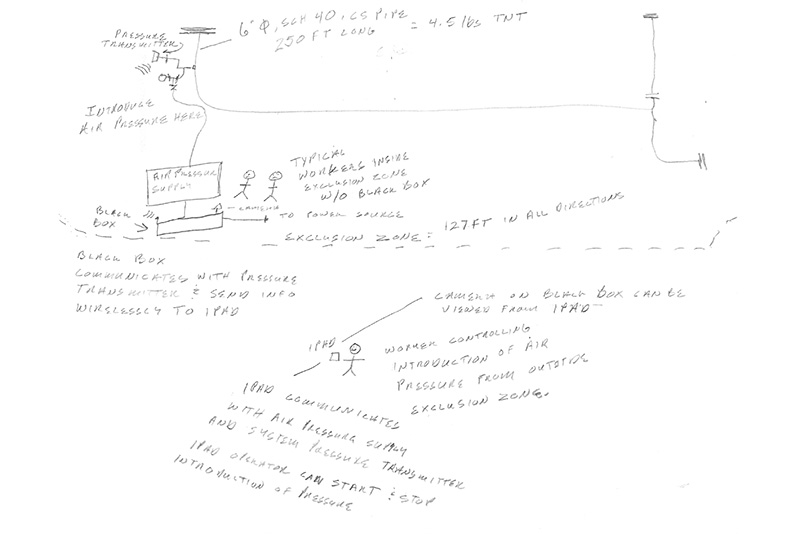

“We have all sorts of connectivity devices, right?” he said. “We can message and coordinate our calendars and talk with each other halfway around the world. So, why wouldn't it be possible for us to come up with a device that can communicate our intentions of opening a valve in letting pressure, then stopping the pressure flow when we need to? That's what started it. I drew a hand sketch that looked like a cartoon that kind of showed what I was trying to say and submitted to The Big Pitch, and everybody thought it was a good idea.”

Weiler was one of five finalists who presented to the Big Pitch panel of judges and one of two chosen to receive funding and support to bring the idea to life.

Dysruptek selected Kickr, a product design, engineering, prototyping, and manufacturing company, to help create the prototype. Weiler worked closely with the Kickr team throughout an engagement that lasted about eight months and produced the first version of the device.

Putting Theory into Practice

RAPTOR works as a flow-control system between the pressure source and the piping system being tested and governs the amount of pneumatic pressure that’s introduced. The inlet hose runs from the gas source to RAPTOR, and the outlet hose connects the device to the system being tested. Everyone is cleared from the exclusion zone, and RAPTOR is activated. From a safe distance, the operator uses a smartphone or tablet interface with the device via Wi-Fi to program the pressure level and time interval.

The standard operating procedure is that RAPTOR’s inlet valve opens, pressurizes the system to a low PSI, and the inlet valve closes. If no pressure is lost after a pre-established time, the valve reopens and increases the pressure. The process is repeated until the pressure is elevated to a test level 10% above the normal operating pressure. If the system remains intact at the test level, the purge valve opens and returns the system to the operating level, where it can be inspected manually. And safely.

Then, and only then, does someone enter the exclusion zone to soap and inspect the joints.

“At that point, not only is it not leaking, but it's been strength tested,” Weiler said. “You know that it’s responding to the hangars and the restraints that are designed in the system. Not only is it not leaking, but it’s been strength tested so that any fitting, any gasket, any flange that's possibly defective or could be a problem; if it's going to fail, it would have already failed.

“We're not exposing anybody to test the pressure. That's the real key. That's when the system is most vulnerable, and that's when you’re going to have a catastrophic failure if it’s going to happen.”

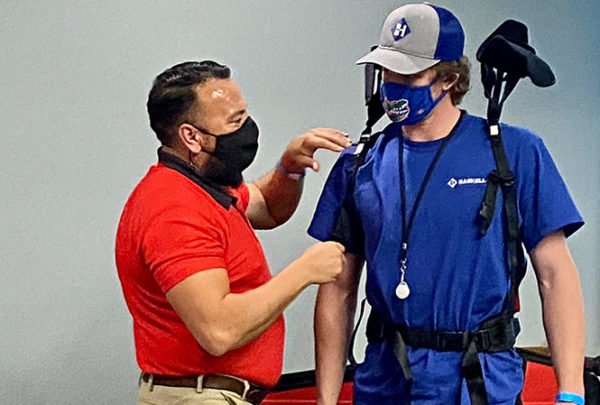

Nearly a year after the inaugural Big Pitch, Dysruptek brought online a proof of concept ready for beta testing. A group that included Dysruptek Managing Director Cutler Knupp, Haskell Director of Innovation Hamzah Shanbari and Weiler created conditions to simulate an actual jobsite pressure test. Weiler said it was an emotional moment for him when it worked exactly as he had envisioned.

“I teared up,” he said. “A lot of times even, even thinking about it still kind of gets me like that. I mean, it's a level of excitement, but at the same time, it's just real hard to describe the emotions that go through my mind.”

Benefits Beyond Safety

Weiler was motivated to create RAPTOR solely by his interest in safety, but there is a strong business case for the newly patented invention, too.

Hydrostatic testing is the main alternative to pneumatic testing. It is used in virtually all high-pressure cases because it involves much lower levels of potential energy and is significantly safer. But it is also more costly and sometimes not a viable option. Now that it can be done safely, pneumatic testing can be a more feasible option – and an advantageous one.

“Perhaps water is an increasingly scarce resource,” Weiler said. “Perhaps the volume used could overwhelm the local water treatment system, or maybe you're not even allowed to put it in the local wastewater system at all, and you have to take it someplace. From an economy of scale, there are a lot of implications beyond the safety point of view. I mean, first and foremost, the purpose is to keep people out of harm's way, but in doing so, we may actually be able to expand to the use of pneumatic testing. And there's a lot of potential there as well.”

A successful proof of concept led Dysruptek to launch the next development phase, creating a minimum viable product that could be field-tested by Haskell crews and select industry partners. After a months-long selection process, the team chose Seattle-based Teague as the industrial designer to create the next iteration.

From that point, Weiler and Robotics & Research Lead Jorge Tubella worked with hardware and software designers to create three second-generation devices, which are built into airline carryon-sized Pelican cases. Ultimately, the roadmap leads to mass production for widespread industry use.

The latest RAPTOR model has been enhanced to prioritize both safety and efficiency in construction operations. Its design allows a single individual to deploy it, and it features easy-to-disconnect components for all attached equipment. Notably, RAPTOR streamlines testing processes, achieving a remarkable 300% increase in speed by minimizing setup time and manpower. In emergencies, RAPTOR's safety mechanism ensures the inlet valve shuts while the purge valve opens, mitigating potential risks. Once the test is complete, the user can purge the system and download the results. In the construction world, RAPTOR stands out, seamlessly blending safety with efficiency, marking a significant step forward for the industry.

From its beginnings in 1965, Haskell has been a design-build pioneer and a leader in architectural, engineering and construction innovation. Earlier in 2023, global insurance carrier AXA XL ranked Haskell No. 1 in its Technology Adoption Maturity Index (TAMI), its proprietary benchmarking system to help contractors measure their tech adoption against an industry index and their peers to determine optimal investment in new construction technology.

RAPTOR is the very essence of Dysruptek’s mission to invest in disruptive architecture, engineering, and construction technologies to reshape the built world and represents another significant milestone achievement in Haskell’s unwavering commitment to safety.

For Gary Weiler, it represents the realization of a dream more than a decade old.

“I’ve got to tell you, it's hard to describe the feeling,” he said. “I'm very excited and, even after all this time, I'm still amazed that it’s actually happened.”

Through Dysruptek, its innovation and venture capital arm, Haskell leads the construction industry in technological development and adoption. Contact the Dysruptek team to discuss your idea “For the Betterment of the Industry.”